| Diagnostics, nanotechnology | |||

Liver cells in silicon crystals screen drugs for toxicity20 June 2006 Researchers at the University of California, San Diego have developed what they call a “Smart Petri Dish” that could be used to rapidly screen new drugs for toxic interactions or identify cells in the early stages of cancer circulating through a patient’s blood.

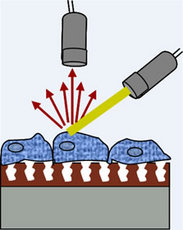

Their invention, described in the June 20 issue of Langmuir, a physical chemistry journal published by the American Chemical Society, uses visible light scattered off porous silicon crystals filled with polystyrene to detect subtle changes in the sizes and shapes of the cells. The liver cells are grown on the polystyrene. “One of the big concerns with any potential new drug is its toxicity,” says Michael Sailor, a professor of chemistry at biochemistry at UCSD who headed the research team. “Since the liver is the organ that cleans up the blood, liver cells are particularly susceptible when a toxin is introduced to the body. Pharmaceutical companies want to know early on the effect a drug has on the liver. But it’s very expensive to screen every potential candidate on living animals, typically rats. So if you can use just a few cells from the liver rather than the entire animal, you can perform many more thorough tests.” “You could also in principle use this to identify metastatic cancer cells circulating in a patient's blood,” Sailor adds, “by putting blood samples from a patient onto the crystal and comparing them to normal blood samples.” In addition, says Michael Schwartz, a postdoctoral scholar in Sailor's laboratory and the first author of the paper: “The potential of our technique for fundamental studies of cell toxicity is exciting, Since we can monitor cells in real time without removing them from their natural environment, the observed changes provide a time course for performing more detailed tests to find out why drugs are toxic.” The scientists constructed their Smart Petri Dish by first fabricating silicon crystals with nanometer-sized holes. This enabled them to produce a photonic crystal, capable of controlling light within the structure analogous to the way that semiconductors transmit electricity through computer chips. By attaching rat liver cells to the polystyrene within the crystals and measuring the scattering of light with a sensitive spectrometer, they were able to detect small changes in the shapes of the cells as they reacted to toxic doses of cadmium chloride and acetaminophen. “As these cells shrivel up in response to a toxin, they scatter light better, much like fog on a car windshield, allowing us to quickly detect which drugs may have adverse side effects when taken in combination with another,” says Sailor. “You’re not supposed to drink alcohol when taking acetaminophen, because the combination of the two is much more toxic to your liver than either drug individually. This is known as an adverse drug-drug interaction and it is very expensive and time-consuming to screen a new drug candidate with all the possible combinations of drugs that a patient may be taking. The Smart Petri Dish allows us to perform a large number of such toxicity assays simultaneously, in order to provide an early indication of the particular physiological or pharmacological conditions that need more in-depth study.” “Although we performed these experiments on rat cells, this technology can be easily extended to human cells,” says Sangeeta Bhatia, a professor of bioengineering at UCSD now at MIT, who also participated in the study. “This is important because we know that the enzymes that metabolize drugs—the P450 family—are very different in animal and humans. This is one of the reasons many drugs clear animal testing but end up toxic in patients. This type of sensor could help us predict human liver responses without patient exposure.” “Because the Smart Petri Dish gives a continuous readout of cell damage,” she adds, “this type of sensor could also be very useful for understanding more about the way environmental toxicants such as water contaminants or viruses like hepatitis cause long-term liver damage.” Others involved in the development include Sara Alvarez, a graduate student in Sailor’s laboratory, and Austin Derfus, a graduate student of engineering in Bhatia’s former UCSD laboratory. UCSD has filed several patent applications on the device, which is now in the process of being commercialized by the Hitachi Chemical Research Center in Irvine, Ca. The design of the new device builds on a previous development in the UCSD laboratories of Sailor and Bhatia that allowed the scientists to maintain fully functioning liver cells in culture. While many cell types can be easily grown in culture dishes, normal liver cells are much more discriminating and quickly die when removed from the body. But by designing a porous silicon chip with miniature wells similar to those in muffin tins, the UCSD researchers were able to mimic the extracellular matrix of the liver and keep the liver cells alive. On this chip, individual cells are contained within well-like structures, 2 to 1,500 nanometres in diameter, or no wider than a human hair, that promote the flow of nutrients and chemicals through the cell culture and filter out larger particles such as bacteria and viruses. This design effectively persuades the cells to behave collectively the way they do in a fully functioning liver. The scientists write in their paper that in their experiments the Smart Petri Dish was able to detect changes in the cells exposed to toxins “before traditional assays are able to detect a decrease in viability, demonstrating the potential of the technique as a complementary tool for cell viability studies.” In addition, they add, their method “is noninvasive and can be performed in real time, representing a significant advantage compared to other techniques for in vitro monitoring of cell morphology,” that is, for monitoring cells in the laboratory, outside of humans or animals. |