Blind patient regains sight with 'eyetooth' implanted in eye

9 October 2009

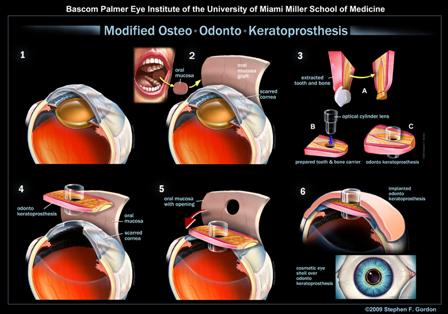

Blind for nine years, Sharron Kay Thornton has regained her sight through a first-in-the-US surgical procedure at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. The procedure — modified osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (MOOKP) — implanted her eyetooth in her eye, as a base to hold a prosthetic lens.

“I’m looking forward to seeing my seven youngest grandchildren for the first time,” said Thornton, 60, of Smithdale, Miss., who was blinded by Stevens-Johnson syndrome in 2000. The rare, serious skin condition destroys the cells on the surface of the eye causing severe scarring of the cornea. “We take sight for granted, not realizing that it can be lost at any moment,” she said. “This truly is a miracle.”

On Labor Day weekend, after the last in a series of surgeries by corneal specialist Victor L. Perez, M.D., associate professor of ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, bandages were removed from Thornton’s eyes and she was able to recognize faces only hours after her surgery. Two weeks following her surgery, she is already reading newsprint with a visual acuity of 20/70 and it is expected to improve further as her surgical scars heal.

The steps in the modified

osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis (MOOKP) in which an eyetooth is impalnted

in the eye as a base to hold a prosthetic lens

(Graphic: Business Wire)

“Through the work of Dr Perez’s team, patients in the United States now have access to this complex surgical technique, which has been available only in a limited number of centers in Europe and Asia,” said Dr Eduardo C. Alfonso, MD, chairman of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute.

Developed in Italy, MOOKP has proven effective as a solution to end-stage corneal disease where severe corneal scarring blocks vision and corneal transplants are no longer an option but the eye’s internal structures and optic nerve remain healthy. Patients may have suffered trauma to their cornea, the outside surface of the eye where a contact lens would sit, from chemical injuries, thermal burns, and inflammatory or autoimmune disorders, such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

“For certain patients whose bodies reject a transplanted or artificial cornea, this procedure ‘of last resort’ implants the patient’s tooth in the eye to anchor a prosthetic lens and restore vision,” explained Dr. Perez. “In Sharron’s case, we implanted her canine tooth, her eyetooth.”

Dr. Perez’s interdisciplinary team included Yoh Sawatari, D.D.S., assistant professor of clinical surgery at the Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Dentistry at the University of Miami/Jackson Memorial Medical Center, who extracted the patient’s canine or “eyetooth” and surrounding bone.

In MOOKP, the tooth and surrounding bone are shaved and sculpted, and a hole is drilled for the insertion of an optical cylinder lens. Next, to bond the tooth and lens as a bio-integrated unit, they are implanted under the patient’s skin in the cheek or shoulder. Meanwhile, the ophthalmologist prepares the surface of the eye for implantation of the prosthesis by removing scar tissue surrounding the damaged cornea.

About one month later, mucous material is collected from the inside of the patient’s cheek and used to cover and rehabilitate the surface of the damaged eye. In the final phase, usually two months later, the prosthesis is removed from the cheek or shoulder and implanted in the eye. The prosthesis is carefully aligned with the centre of the eye, and a hole is made in the mucosa for the prosthetic lens, which protrudes slightly from the eye and enables light to re-enter the eye allowing the patient to see once again.

For Thornton, the surgery marked the successful conclusion of a nine-year medical odyssey that started at the onset of Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Six years ago, a friend drove Thornton 900 miles to Bascom Palmer for an ophthalmic evaluation. A stem cell procedure was performed, but proved unsuccessful. Since she was not a candidate for a cornea transplant, she was referred to Dr Perez, another Bascom Palmer surgeon who was exploring the possibility of the MOOKP technique.

“I’m so thankful that the doctors at Bascom Palmer never gave up on me – they kept searching,” said Thornton. Last year, Dr. Perez traveled to Europe for training by Italian ophthalmologist Giancarlo Falcinelli, M.D., who developed the MOOKP procedure, building on the original OOKP technique developed in the 1960s by Professor Benedetto Strampelli, M.D., also of Italy.

Now Thornton is excited about seeing her three grown children and nine grandchildren — as well as rediscovering simple joys like watching clouds and playing cards again with friends. “Without sight, life is really hard. I’m hoping this surgery will help countless people,” she said.

Bookmark this page